The "Lottery Ticket" Illusion: Why Picking Winners is Harder Than You Think

I'm writing this article to encourage those of you holding large positions in individual tech stocks to reconsider, or at least be aware of the risks. 😜

If you’ve looked at your portfolio recently—especially if you’re holding major tech stocks like Nvidia or Google—you’re probably feeling pretty good. We’re living through a period of incredible market performance driven by a handful of massive companies that seem invincible. It honestly feels like you can’t lose by betting on the biggest names in the room.

But as a financial planner, I’ve seen this movie before. The vibe today—that feeling that "this time is different" and that tech stocks are a one-way ticket to wealth—feels a lot like the euphoria of 2000 right before the dot-com bubble burst. I'm not saying we're in a bubble per se, but the words I hear eerily echo those I heard back then. I remember distinctly a conversation with a family member in their driveway, who had just invested $20k in a stock (it was NetApp if you must know). I asked him if he knew anything about NetApp, as I just finished my master's thesis on the storage tech industry. He said, "I haven't the faintest idea, but I know I'm making a killing on it!" This person lost well over a million dollars in the next 12 months.

It’s totally natural to look at skyrocketing graphs and feel like you’re missing out if you aren’t picking the next big winner. But relying on individual stock picks for your long-term financial security isn’t really investing. Statistically speaking, it’s closer to buying lottery tickets.

The "Coin Flip" Fallacy: The Odds Are Not 50/50

When you buy a stock, it feels like a 50/50 shot: it’ll either beat the market, or it won’t. But the math doesn't actually work that way. The odds of picking a market-beating stock are historically worse than a coin flip.

According to S&P Dow Jones Indices, the vast majority of stocks underperform the average. From the beginning of 2001 through September 2025, only 19% of the companies in the S&P 500 actually outperformed the average stock’s return.

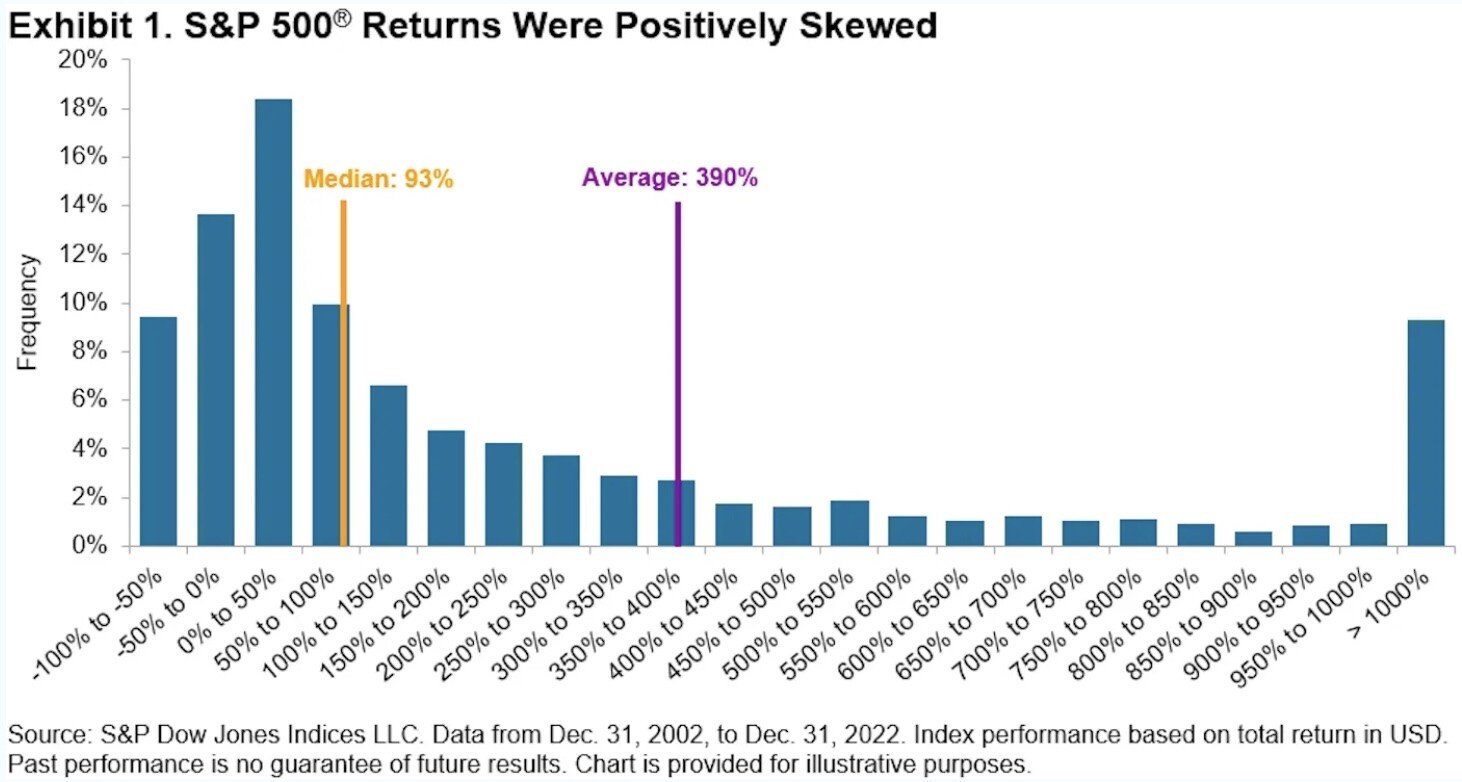

"Positive Skew" results in the average stock return being significantly higher than the median.

Why so low? It comes down to something called "positive skew". In the market, the most you can lose is 100% of your money (the left tail), but your upside is theoretically unlimited (the right tail). Because a tiny minority of stocks generate massive returns, they significantly pull the market average up.

The result is that the "average" return is way higher than the "median" return. Since 2001, the median stock return has been just 59%, while the average has been 452%. If you’re picking individual stocks, you aren't just trying to find a profitable company; you’re trying to find the needle in the haystack that drives that massive average. If you miss those few "super stocks," your portfolio is likely to lag far behind.

The Tech Trap: Even Innovators Don't Win Forever

A common counter-argument I hear from tech employees is, "I'm not buying random stocks; I'm buying the companies I understand." The trap here is assuming that because you understand the technology, you somehow know more about what will drive their stock price than everyone else. Remember you're competing with people who do this for a living, and they have the time, resources, and determination to beat you at it. And still they struggle to beat the market. Don't assume it's a given that a company with dominant technology and a massive run-up will stay a winner forever. History shows us that even the most "inevitable" tech giants can suddenly turn into dead weight in your portfolio.

The Academic Verdict: Most Stocks Are "Crummy" Investments

The definitive research on this comes from Professor Hendrik Bessembinder of Arizona State University. His findings are pretty sobering for anyone trying to build a retirement plan on individual picks.

In a well known 2017 paper, he observed that the majority of individual stocks have historically been "crummy" investments that actually underperformed Treasury bills. In a follow-up, he found that the top-performing 2.4% of firms accounted for all of the net global stock market wealth creation from 1990 to 2020. This is why index funds (ETFs) are so powerful. When you buy an S&P 500 ETF, you’re guaranteed to hold those top 2.4% of companies that drive the returns. When you try to pick stocks yourself, you’re betting your financial future that you can identify that 2.4% in advance.

Even the Pros Can't Keep the Streak Alive

You might be thinking, "But I'm smart, I do my research, and I’ve picked winners before." The problem isn't picking a winner once; it's doing it consistently over the decades you need for retirement. If you're under 40 years old, there's likely to be a major stock market collapse and recession before you retire. And those high-flying tech stocks are likely to take a bigger hit than the market average.

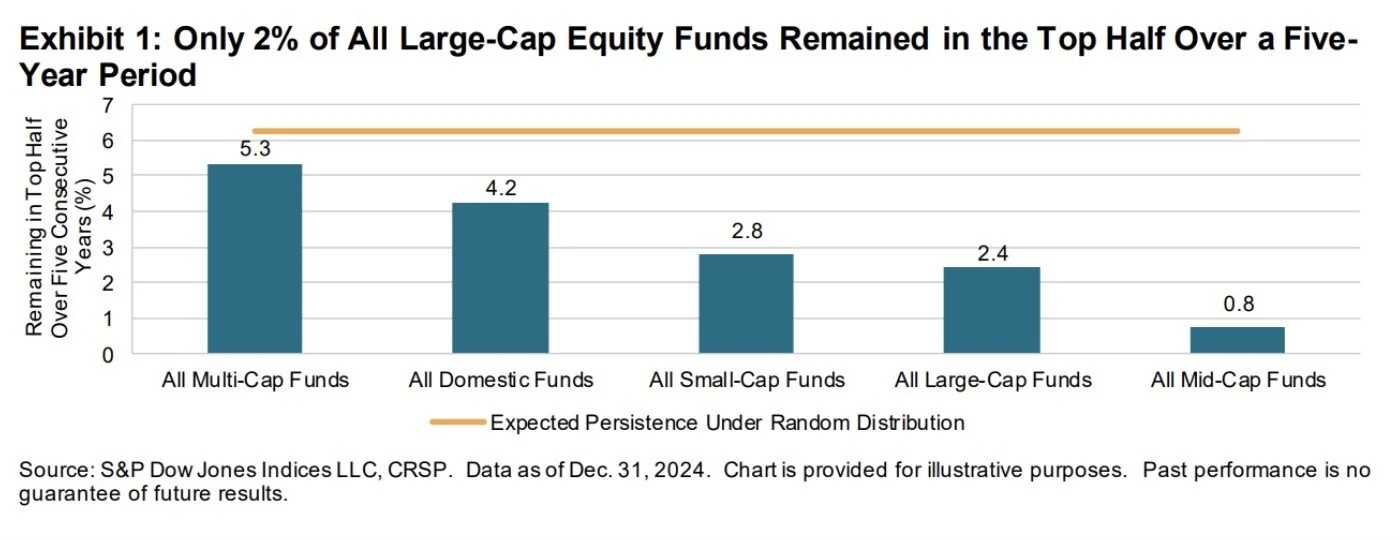

S&P Dow Jones Indices publishes a "Persistence Scorecard" that tracks whether top-performing fund managers can keep winning. These are the people who do this for a living and have the resources necessary. And yet, the results are not good:

Luck runs out fast: Of the large-cap equity funds that were in the top half of performance in 2022, only 12.43% stayed in the top half in 2023.

The 5-year cliff: Just 4.21% of all U.S. equity funds that started in the top half remained there for the next 4 years.

Zero persistence at the top: Perhaps most shockingly, not one of the large-cap funds remained in the top quartile of performance over a five-year period ending in 2024.

If professional fund managers, armed with armies of analysts, can’t stay at the top for even five years, we have to be realistic about our own chances. As the analysts at S&P noted, "Skill is likely to persist, but luck is ephemeral."

The Trap of "Recency Bias" and 1999 Deja Vu

The current market makes this advice hard to swallow. When almost everything is going up, stock picking feels easy. It feels like skill. But historically, about 69% of stocks underperform the index over the long run. The recent rally is the exception, not the rule.

Legendary investor Warren Buffett has been open about this. In his 2023 annual letter, he admitted that his massive success was the product of only "about a dozen truly good decisions" over a lifetime—about one every five years. He noted that "the weeds wither away in significance as the flowers bloom," meaning his few massive winners carried the dead weight of his many mistakes.

Unless you have the capital and patience of Warren Buffett to wait decades for a dozen "flowers" to bloom, a concentrated portfolio is a dangerous risk.

The "Boring" Path to Top-Tier Returns

So, what's the solution? It’s shifting your mindset from "beating the market" to "capturing the market." By diversifying into broad-based ETFs, you’re essentially accepting the "average" return. But being "average" consistently actually makes you an elite investor.

Because most active stock pickers underperform (91% of active managers underperformed over 20 years ), simply holding the index puts you ahead of the vast majority of pros.

As investment writer Barry Ritholtz puts it, "Consistent average returns turn into above-average returns over time". You eliminate the risk of holding the "weeds" that go to zero, and you guarantee you'll always own the "flowers"—the top 2.4%—because they’re automatically included in the index.

The Takeaway

I wrote this to present the case for avoiding holding individual stocks. It's not a moral imperative, but a rational guideline based on the statistical evidence over long periods of time. I know there's a strong intuitive sense to continue holding individual stocks that have done well. It's not easy to argue against 10 million years of evolutionary biology embedded in our amygdalas. I only ask that you consider the risks and maybe balance out the lottery tickets with your other, more diversified investments.

Disclaimer: The information provided in this blog post is for educational and informational purposes only and does not constitute specific financial, tax, or legal advice. All investing involves risk, including the potential loss of principal. Market data and statistics cited are believed to be accurate as of the date of publication, but are subject to change. Please consult with a qualified financial professional to discuss your individual circumstances and risk tolerance before making any investment decisions.